By Keith Kosel, Executive Advisor at Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation

We ask this type of question every day. For example, we may ask― “Is this product that I purchased making a difference?” or “Is this advanced training that I completed making a difference?” Implicit in this common question is the expectation that because we have made an investment in something to achieve a result, the result should be better or more improved than the pre-investment state. So too with a Connected Community of Care (CCC). As I have discussed in previous blogs, establishing a CCC requires a substantial investment in both time and money. Therefore, it is only natural to ask― “Is this CCC making a difference, and how would I know?” Unfortunately, most CCCs are established with very little forethought given to this exact question. While we expect the CCC will help community residents improve their health and well-being, how will we know conclusively that this has happened? How will we demonstrate its impact to a potential partner or― more importantly― a funder? This is where data, measurement, and evaluation come into play. For most people, these three words cause anxiety levels to immediately rise. But this doesn’t need to be the case; a little planning and forethought can go a long way to assuaging one’ anxiety when asked the question, “Is your CCC making a difference?”

Before we think about what data we will need to answer this question or how we will collect it, we first need to establish what we mean by “making a difference”. Understand, there is no one correct answer to this question. What may constitute a positive difference or impact for one organization may be much different for another, even similar organization. Many factors contribute to the final answer and each are usually organization-, ecosystem- and situation-specific.

In practice, there are many ways to define making a difference. First, we can look at quantitative or numeric information to make this determination. Are we providing more nutritious meals to indigent residents? Is the number of inappropriate Emergency Department visits declining or, conversely, is the number of residents having visits with a primary care provider increasing? All of these effects can be counted and judged against some predefined goal (more on this later). Second, we can assess making a difference by asking the people that are being touched by the CCC. Through surveys or brief interviews, community residents can tell you in their own words what impact, if any, the CCC has on their lives. While this qualitative (non-numeric) information can often be more informative than simple quantitative information because it represents the voice of the individual, to answer the question of whether your CCC is making a difference, you will also still likely need to establish numeric goals. A third way to assess whether your CCC is making a difference is indirectly via the financial and non-financial opportunities that arise as a result of having a CCC versus not having one. For example, having a CCC may make it much easier to perform contact tracing among vulnerable populations during a pandemic like COVID-19.

Having a CCC may also enable a healthcare system or a community-based organization (CBO) to apply for a grant that it otherwise might not be competitively positioned to do if it did not have an integrated system of healthcare and social service providers such as a CCC.

Regardless of the approach to define making a difference, the importance of planning for 1) what things will be measured to generate the necessary data, 2) how and when that measurement will take place, and 3) how the resulting data will be analyzed and evaluated, cannot be underestimated.

Similarly, these decisions cannot be put off until a later date as is often seen with start-ups, including CCCs. While it is natural to want to focus on the more immediate needs associated with launching a CCC, deferring the question of how we will know if the entity is making a difference can prove costly, both from an operational and financial perspective. At the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) we encourage those planning a CCC to devote the necessary time early on to setting performance goals and objectives and determining how and when they will be measured and evaluated. While it is important to explicitly build this step into your CCC planning phase, the scope and scale of the work does not have to be extensive. In fact, at PCCI we strongly encourage CCCs to start small with a limited set of goals, objectives, and requisite measures and then scale up as the CCC grows and matures. This approach has the dual benefit of providing essential core information early on while also not overwhelming the CCC staff with data collection activities that may be a distraction from more pressing, day-to-day activities.

Based on this author’s work with literally hundreds of healthcare and social service provider organizations, experience suggests that most entities (both new and established organizations) do best if they initially establish 1) a limited number of goals― one or two at most, 2) a similar number of objectives to achieve each goal, and 3) no more than three to four performance measures to support each goal. While this may seem like an insufficient number of performance elements in today’s data-obsessed world, remember that you can always add additional goals, objectives, and measures as your expertise and comfort levels allow and as your CCC evolves.

Even more important than the numbers, however, it is essential to get the selection of the goals, objectives, and performance measures correct. Each of these three performance elements plays an essential role in helping you answer the question “Is my CCC making a difference?” Your goals focus on the long-term― what do you ultimately want to happen, while your objectives are the short-term accomplishments that help you achieve your goals. In both cases, you must be sure that what you are expecting is both realistic and appropriate for your CCC’s stage of development. For example, assuming a newly established CCC will reduce ED utilization in its first year or two may not be reasonable and may lead to frustration and disillusionment if the goal is not achieved. If you select a BHAG (Big Harry Audacious Goal), you must allow sufficient time (and then some) for all the necessary pieces to come together. The rule of thumb for large-scale demonstration projects such as launching a CCC is that they 1) take (much) longer than expected, 2) cost more than budgeted, and 3) generally initially deliver less than expected. These facts should not dissuade you from your journey, but rather help you keep things in perspective as the project evolves to one that in the long-term is viewed as valuable in achieving your goals.

If getting the goals and objectives correct is important, then selecting the correct performance measures and designing a feasible measurement plan is paramount. Here again, quality is more important than quantity. A few well-chosen performance measures, implemented correctly, will generate far more in the way of actionable data than a plethora of randomly selected measures. To optimize your ability to assess if your CCC is making a difference, your performance measures should be collected at regular intervals following the launch of the CCC. While many established programs collect, analyze, and evaluate performance data on a quarterly basis, for fledgling CCCs, PCCI recommends this data be collected monthly for at least the first one to two years or until the CCC reaches a stable level of operations. While monthly data collection requires a little more work, the more frequent feedback allows you to make necessary program or operational modifications more quickly and with fewer disruptions than that afforded with quarterly feedback. If measurement and evaluation is an area where you don’t have a lot of experience, reach out to others that do, especially individuals and organizations such as PCCI that have experience assessing performance in large-scale, multi-sector collaborative projects.

While we all hope that the answer to the question “Is my CCC making a difference” is yes, the answer may be no early on in the life of a CCC. As disheartening as this news may be, it’s important to not give up, but to look critically at what is working and what is not and make adjustments where necessary. Usually, this examination does not necessitate a complete “reboot” of the CCC initiative, but rather requires making minor changes accompanied by paying closer attention to the CCC’s operations. Seek feedback from your staff and those you serve and be open to change, where change is warranted. As indicated, these types of projects take a lot longer to reach fruition than most people believe, but with a solid plan, patience, and flexibility, you will be able to answer, “Yes, my CCC is definitively making a difference in the lives of the community residents it serves.”

About the author

About the author

Dr. Keith Kosel is an Executive Advisor at Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) and is co-author of “Building Connected Communities of Care: The Playbook for Streamlining Effective Coordination Between Medical and Community-Based Organizations,” a guide that brings together communities to support our most vulnerable. At PCCI, Keith is leveraging his passion for – and extensive experience in – patient safety, quality, and population health by focusing on understanding Non Medical Drivers of Health and the impact of community-based interventions in improving the health of vulnerable and underserved populations.

Delta variant.

Delta variant.

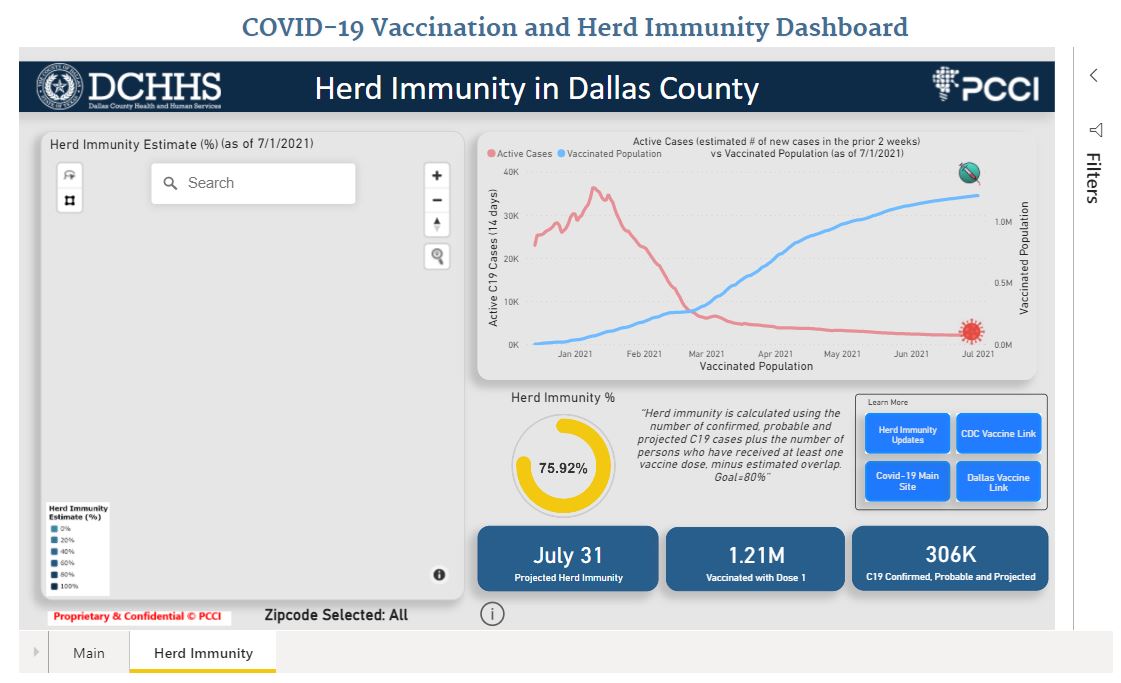

The COVID-19 Vaccination and Herd Immunity Dashboard provides exclusive data for Dallas County, including herd immunity by percentage of the county’s population at the ZIP code level. This is helpful for monitoring the county’s efforts to drive vaccination efforts to reach the herd immunity threshold of 80 percent of the whole county’s population who either have recovered from COVID-19 or who have received vaccinations. The dashboard’s data also includes vaccinations by manufacturer, estimated active COVID cases and important information resources about the pandemic.

The COVID-19 Vaccination and Herd Immunity Dashboard provides exclusive data for Dallas County, including herd immunity by percentage of the county’s population at the ZIP code level. This is helpful for monitoring the county’s efforts to drive vaccination efforts to reach the herd immunity threshold of 80 percent of the whole county’s population who either have recovered from COVID-19 or who have received vaccinations. The dashboard’s data also includes vaccinations by manufacturer, estimated active COVID cases and important information resources about the pandemic.

About the author

About the author

“Thanks to the vaccination programs implemented throughout Dallas County, we continue to see progress in our fight against COVID-19,” said Thomas Roderick, PhD, Executive in Residence at PCCI. “Our latest Vulnerability Index report is the most positive yet, with new cases slowing and modest, but important participation in the vaccination program continuing. This progress is a credit to the outstanding efforts of our public health leaders and residents devoted to crushing COVID.”

“Thanks to the vaccination programs implemented throughout Dallas County, we continue to see progress in our fight against COVID-19,” said Thomas Roderick, PhD, Executive in Residence at PCCI. “Our latest Vulnerability Index report is the most positive yet, with new cases slowing and modest, but important participation in the vaccination program continuing. This progress is a credit to the outstanding efforts of our public health leaders and residents devoted to crushing COVID.” Data Sources:

Data Sources: