By Keith C. Kosel, PhD, MHSA, MBA

Vice President, Enterprise Relationships

This question initially brings to mind many possibilities such as connection to the latest 5G cellular service, a new super-fast internet provider, or maybe one of the many new energy suppliers jockeying for market share from traditional utility companies. While all of these might represent legitimate opportunities to improve one’s community, here we are talking about a different concept; specifically, whether your community is ready to have a Connected Community of Care (CCC) to advance whole person health.

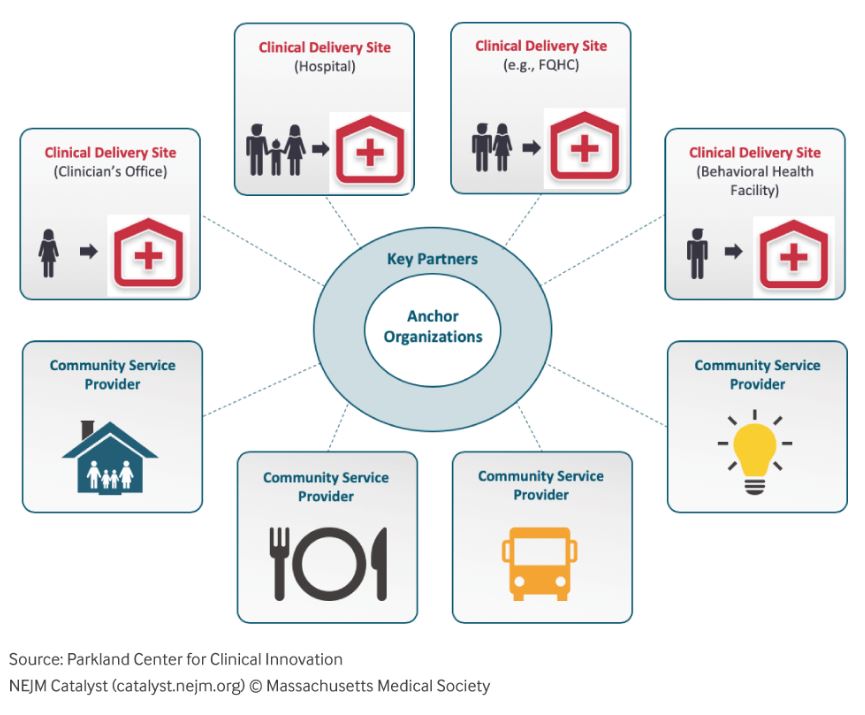

The image of a CCC may seem obvious. After all, we all live in communities where we have some connections between hospitals, physician practices, ambulatory care centers, and pharmacies to name just a few. But here we are talking about a broader sense of connected community that includes not just health care organizations, but social service organizations, such as schools and civic organizations and community-based organizations (CBOs) like neighborhood food pantries and temporary housing facilities. A true CCC links together local healthcare providers along with a wide array of CBOs, faith-based organizations and civic entities to help address those social factors, such as education, income security, food access, and behavioral support networks, which can influence a population’s risk for illness or disease. Addressing these factors in connection with traditional medical care can reduce disease risk and advance whole person care. Such is the case in Dallas Texas, where the Dallas CCC information exchange platform has been operating since 2012. Designed to electronically bring together local healthcare systems, clinicians, and ancillary providers with over a hundred CBOs, the Dallas CCC provides a real-time referral and communication platform with a sophisticated care management system designed and built by the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) and Pieces Technologies, Inc.

The image of a CCC may seem obvious. After all, we all live in communities where we have some connections between hospitals, physician practices, ambulatory care centers, and pharmacies to name just a few. But here we are talking about a broader sense of connected community that includes not just health care organizations, but social service organizations, such as schools and civic organizations and community-based organizations (CBOs) like neighborhood food pantries and temporary housing facilities. A true CCC links together local healthcare providers along with a wide array of CBOs, faith-based organizations and civic entities to help address those social factors, such as education, income security, food access, and behavioral support networks, which can influence a population’s risk for illness or disease. Addressing these factors in connection with traditional medical care can reduce disease risk and advance whole person care. Such is the case in Dallas Texas, where the Dallas CCC information exchange platform has been operating since 2012. Designed to electronically bring together local healthcare systems, clinicians, and ancillary providers with over a hundred CBOs, the Dallas CCC provides a real-time referral and communication platform with a sophisticated care management system designed and built by the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) and Pieces Technologies, Inc.

Long before this information exchange platform was implemented, the framers of the Dallas CCC came together to consider whether Dallas needed such a network and whether the potential partners in the community were truly ready to make the commitments needed to bring this idea to fruition. As more and more communities and healthcare provider entities realize the tremendous potential of addressing the social determinants of health by bringing together healthcare entities and CBOs and other social-service organizations, the question of community readiness for a CCC is being asked much more often. But how do you know what the right answer is?

Before looking at the details of how we might answer this, let’s remember that a CCC doesn’t don’t just happen in a vacuum. It requires belief, vision, commitment― and above all― alignment among the key stakeholders. Every CCC that has formed, including the Dallas CCC, begins with a vision for a healthier community and its citizens. This vision is typically shared by two or more large and influential key community stakeholders, such as a large healthcare system, school district, civic entity, or social- service organization like the United Way or Salvation Army. Leaders from these organizations often initially connect at informal social gatherings and advance the idea of what if? These informal exchanges soon lead to a more formal meeting where the topic is more fully discussed and each of the participants articulates their vision for a healthier community and what that might look like going forward. This stage in the evolution of a CCC is perhaps the key step in the transformation process, as while all stakeholders will have a vision, achieving alignment among those visions is no small feat. Many hopeful CCCs never pass this stage, as the stakeholders cannot come to agreement on a common vision that each can support. For the fortunate few, intrinsic organizational differences can be successfully set aside to allow the CCC to move forward.

It’s at this point in the CCC’s evolution that details begin to matter in truthfully answering the question, “Is this community ready to be connected?” While there may be agreement among the key stakeholders on a vision, the details around readiness may still divert or delay the best-laid plans. It is safe to say that the key to understanding a community’s readiness to form a CCC lies in the completion of a formal, comprehensive, and transparent readiness assessment. A readiness assessment is a process to collect, analyze, and evaluate critical information gathered from the community to help identify actual clinical and socio-economic needs, current capabilities and resources (including technology), and community interest and engagement. Taken together, a comprehensive readiness assessment can help identify a community’s strengths and weaknesses in preparation for establishing a CCC. A readiness assessment is not a tactical plan for building a CCC, nor is it a governance document that provides how all members of the CCC will relate to each other. Instead, the readiness assessment provides communities interested in establishing a CCC with an honest and unbiased yardstick to measure preparedness. Conducting and using the results of the readiness assessment is one of the best ways to ensure a successful CCC deployment.

A typical CCC readiness assessment covers five areas: (1) community demographics; (2) clinical areas of need (including trends); (3) social areas of need (including trends); (4) technology competency (e.g., what percent of the potential network participants are computer literate?), availability (e.g., what percent of the potential network participants have internet access?), and suitability (e.g., is the internet access, high speed?); and (5) what are the needs of potential network participants and can these be modeled as use cases for the information exchange network? This information is essential to help key stakeholder decision-makers decide to move forward with establishing a CCC and to know what specific challenges may lie ahead.

The collection of this essential information can be done in a number of ways, such as making use of existing publicly reported data or conducting surveys, interviews, focus groups and townhall meetings with community leaders and residents and clinical and CBO leaders and staff. Experience conducting the readiness assessment that provided the foundation for the Dallas CCC showed that no single information-collection method was sufficient to collect the necessary level and robustness of the data. In Dallas, we utilized all five approaches but found that in addition to researching publicly available data, initial surveys, followed by interviews and focus groups, yielded the most voluminous and reliable information to chart the course ahead.

In addition to the various methods to collect this essential information, the key to obtaining useful and reliable information requires a sufficient number of respondents/participants who are drawn from various organizations and organizational levels. Simply put, you must have a large enough sample and you must have diversity within the sample. It’s not enough to just interview leaders of potential network participants, as their understanding of the needs, trends, and capabilities may look very different from that of front-line staff. Similarly, surveying only one category of potential network participants may not provide enough information to fully understand the socio-economic needs in the community or even the perspectives surrounding the prevalence of chronic conditions. Beyond the qualitative methods involved, it is important to note that if done right, this process takes a lot of time to complete. Cutting corners by reducing the sample size, for example, or doing selective sampling to speed the readiness assessment process along will only cause problems later when this insufficient information results in erroneous decision-making.

Once the data has been collected, it is important to carefully analyze what the data is trying to tell you. Results of the readiness assessment must be shared openly and honestly with all key stakeholders, particularly those serving in a governance capacity. The governance group (a topic for another day) that has formed in parallel with the readiness assessment must be able to evaluate and understand the main messages from the readiness assessment to make an informed decision as to whether to move forward with establishing a CCC. Like the need for alignment around the key stakeholder’s vision for the CCC, there must be universal agreement by the key stakeholders as to the message of the readiness assessment and its implications for the road ahead. As with the vision alignment stage, substantive disagreements among the group at this stage are a sign of trouble ahead unless differences can be resolved.

At this point you might be thinking that this all seems very complicated and fraught with potential land mines waiting to derail your effort to answer the original question “Is your community ready to be connected?” Again, I would emphasize the importance of unwavering commitment and alignment to achieve the vision. But I would also offer advice gleaned from working in the CCC space for the last eight years, which is to get help early and don’t wait until the horse is out of the barn! We have seen first-hand many communities and consultants approach the conduct of a readiness assessment with a cavalier attitude, often exemplified by the statement, “we already know all of this,” only later to have to backtrack their pronouncements at substantial additional cost in time and resources. Fortunately, today there are a number of excellent organizations, including PCCI, with the experience, credibility, and integrity in the CCC space to help you on this journey. Don’t be afraid to seek them out. It will be a wise investment that you will not regret, particularly when you begin to see the results of improved whole person health and well-being in your community.

About the author

About the author

Dr. Keith Kosel is a Vice President at Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) and is author of “Building Connected Communities of Care: The Playbook for Streamlining Effective Coordination Between Medical and Community-Based Organizations,” a guide that brings together communities to support our most vulnerable. At PCCI, Keith is leveraging his passion for – and extensive experience in – patient safety, quality, and population health by focusing on understanding social determinants of health and the impact of community-based interventions in improving the health of vulnerable and under-served populations.

###

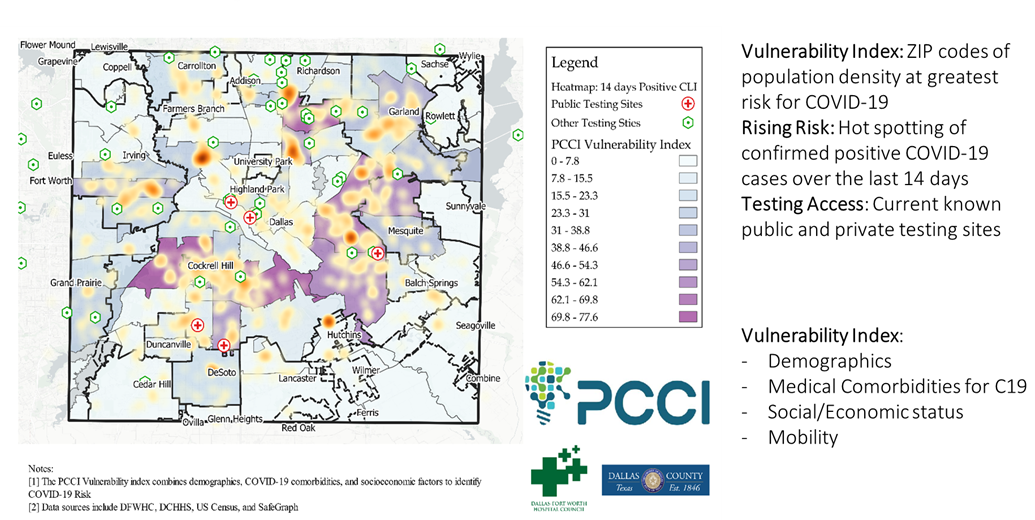

Launched in June, PCCI’s

Launched in June, PCCI’s

hat includes people moving and gathering. For much of the county the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases began to slow in August, compared to July. With no holidays in August, there were fewer large gatherings and travel. These two factors can account for overall decrease across the county. Those areas experiencing increases in vulnerability ratings are largely attributed to yearly increases in mobility and to ongoing COVID-19 hotspots in a particular ZIP code.”

hat includes people moving and gathering. For much of the county the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases began to slow in August, compared to July. With no holidays in August, there were fewer large gatherings and travel. These two factors can account for overall decrease across the county. Those areas experiencing increases in vulnerability ratings are largely attributed to yearly increases in mobility and to ongoing COVID-19 hotspots in a particular ZIP code.”

About the author

About the author