Statement from PCCI CEO Steve Miff:

“On July 4, Dallas County reached the 80 percent herd immunity threshold. This threshold is made up

by 46.6 percent of the total population being vaccinated and 48.7 percent of the population with natural immunity having recovered from being infected by COVID-19.

While this represents good progress, it is important that we understand the work is not over. We must continue to push for vaccinations so COVID and its variants can’t again take hold and diminish the progress we’ve made. Reaching the 80 percent herd immunity rate is not like flipping a switch, but a continuum in our journey. It is an important accomplishment which is a credit to the residents and public health leaders who have committed themselves to crush COVID. While the whole community in average reached the 80 percent mark, there are only 49 ZIP codes above the 80 percent threshold with 45 ZIP codes still below the 80 percent mark. There are still significant pockets in the community that remain vulnerable.

How we got here

The calculations used to measure heard immunity track individual level data for both vaccinations administered and COVID test results since the beginning of the pandemic. For those infected, yet not tested there are a 4x Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio [AIRR] for the adult population and 5x for the pediatric group based on national and local seroprevalence data. The model also calculates an overlap 28 percent of vaccinated population of Dallas estimated to have had prior COVID-19 infection and recovered.

Delta Variant

Further, the current Delta variant is predicted to make up about 25 percent of COVID-19 cases locally, doubling approximately every two weeks. In one month, that could put the Delta variant in the range that has caused a new wave in infections in the UK, though their estimated immunity was below the herd immunity threshold for Delta.

The significantly higher viral loads and more infectious nature of the Delta variant could put the herd immunity target as high as 88 percent to suppress infection spikes when the Delta variant becomes the dominant variant in a few weeks’ time.

Vaccinations Lag

As a county, we’re still behind on vaccinations: Only 38 percent of the total population with completed vaccination series and 47 percent of the total population with at least one dose (61 percent of adults and 80 percent of those over the age of 65 years). While previous infections and partial vaccinations do provide a level of protection, all evidence suggests that full vaccinations are the most effective way to stay safe against the delta variant.

Why is getting vaccinated still very important:

- Infections remain very low for those vaccinated – local data from Parkland and the Dallas County Health & Human Services Department suggests an infection rate of only 0.04 percent for those vaccinated. Getting vaccinated doesn’t only protect you, but those around you, including the children who are not yet eligible for a vaccine.

- Long COVID (prolonged COVID related symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, muscle pain, shortness of breath, and loss of taste and smell) is prevalent in 10-30 percent of those infected and mortality for those unvaccinated is still a concern. Not getting vaccinated is rolling the dice on dying or dealing with long-term medical issues.

The message is simple: don’t wait to get vaccinated. For those still hesitant, the safety and efficacy studies to date are overwhelmingly positive. There are also two key upcoming milestones that should give further confidence to those who remain hesitant: Full FDA approvals for the mRNA vaccines expected in the upcoming weeks and approval for the under 12-year-old groups in the fall.”

-Steve Miff, PhD, President & CEO of Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI)

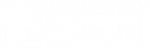

To monitor herd immunity and vaccination progress in Dallas County go to PCCI’s COVID-19 Vaccination and Herd Immunity Dashboard hosted on the Dallas County Health and Human Services’ website: https://www.dallascounty.org/covid-19/.

Background on PCCI’s herd immunity measurements

PCCI’s forecast for herd immunity is based on an innovative yet vetted statistical and immunological model and analysis of spread and management of diseases within communities. Further, PCCI’s 80 percent range for reaching herd immunity is in line with national estimates, such as that of Anthony S. Fauci, MD, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who recently gave a range of 70 to 90 percent and the World Health Organization which gave a 60 to 70 percent range of infections and vaccines to reach herd immunity*.

PCCI’s forecast and estimates have been developed in coordination with community health leaders in Dallas County, including the DCHHS and Parkland Health & Hospital System. Recently, PCCI has been collaborating with the leadership and expert teams at the Institute for Health Improvement on modeling.

*New York Times, Dec. 24, 2020: “How Much Herd Immunity Is Enough?”

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/24/health/herd-immunity-covid-coronavirus.html

The COVID-19 Vaccination and Herd Immunity Dashboard provides exclusive data for Dallas County, including herd immunity by percentage of the county’s population at the ZIP code level. This is helpful for monitoring the county’s efforts to drive vaccination efforts to reach the herd immunity threshold of 80 percent of the whole county’s population who either have recovered from COVID-19 or who have received vaccinations. The dashboard’s data also includes vaccinations by manufacturer, estimated active COVID cases and important information resources about the pandemic.

The COVID-19 Vaccination and Herd Immunity Dashboard provides exclusive data for Dallas County, including herd immunity by percentage of the county’s population at the ZIP code level. This is helpful for monitoring the county’s efforts to drive vaccination efforts to reach the herd immunity threshold of 80 percent of the whole county’s population who either have recovered from COVID-19 or who have received vaccinations. The dashboard’s data also includes vaccinations by manufacturer, estimated active COVID cases and important information resources about the pandemic.

“Thanks to the vaccination programs implemented throughout Dallas County, we continue to see progress in our fight against COVID-19,” said Thomas Roderick, PhD, Executive in Residence at PCCI. “Our latest Vulnerability Index report is the most positive yet, with new cases slowing and modest, but important participation in the vaccination program continuing. This progress is a credit to the outstanding efforts of our public health leaders and residents devoted to crushing COVID.”

“Thanks to the vaccination programs implemented throughout Dallas County, we continue to see progress in our fight against COVID-19,” said Thomas Roderick, PhD, Executive in Residence at PCCI. “Our latest Vulnerability Index report is the most positive yet, with new cases slowing and modest, but important participation in the vaccination program continuing. This progress is a credit to the outstanding efforts of our public health leaders and residents devoted to crushing COVID.” Data Sources:

Data Sources:

“After the holidays, we had vulnerability index ratings at nearly 200, which meant the COVID-19 virus was running rampant through our community,” said George “Holt” Oliver, MD, Vice President of Clinical Informatics at PCCI. “It is a great relief to see that the highest vulnerability index rating now is only 16.91. This is a triumph for our county’s public health leaders, providers and residents who have made the sacrifices and efforts needed to bend the curve.”

“After the holidays, we had vulnerability index ratings at nearly 200, which meant the COVID-19 virus was running rampant through our community,” said George “Holt” Oliver, MD, Vice President of Clinical Informatics at PCCI. “It is a great relief to see that the highest vulnerability index rating now is only 16.91. This is a triumph for our county’s public health leaders, providers and residents who have made the sacrifices and efforts needed to bend the curve.” Currently, the 75150 ZIP code, at the intersection of Interstate Highway 30 and 635 has the highest COVID-19 risk at 16.91, down from a high of 107.30 in January. The ZIP code 75204, in east downtown Dallas, has the second highest vulnerability level at 15.81, down from a high of 126.5 in January.

Currently, the 75150 ZIP code, at the intersection of Interstate Highway 30 and 635 has the highest COVID-19 risk at 16.91, down from a high of 107.30 in January. The ZIP code 75204, in east downtown Dallas, has the second highest vulnerability level at 15.81, down from a high of 126.5 in January.