PCCI’s Community Vulnerability Compass Delivers Actionable Data to Municipal, Community-Based Organizations and Healthcare Providers

By Lance Rather, Senior Director, Product & Strategic Partnerships, PCCI

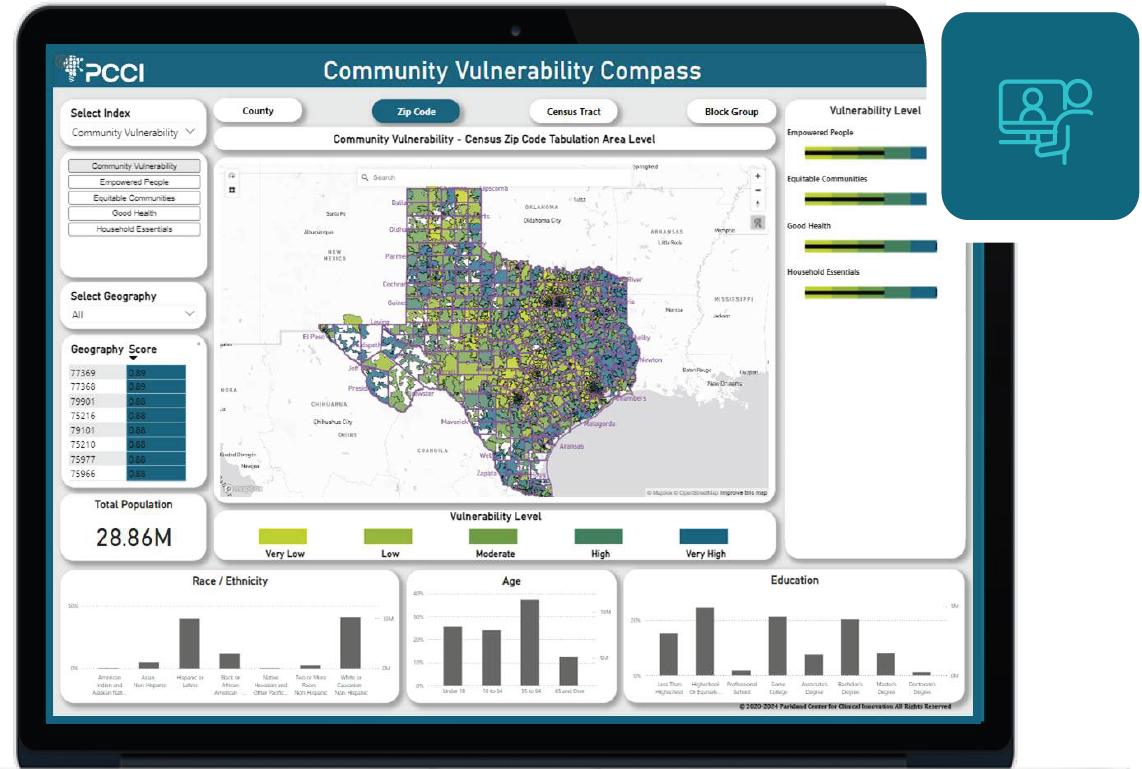

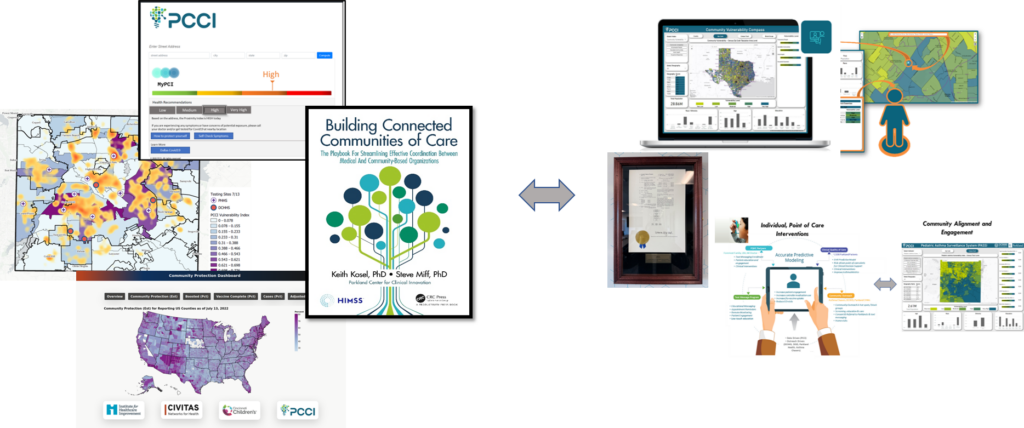

My goal, as part of a healthcare innovation organization, has always been to find factual and data-backed understanding of the community I’m trying to serve. At PCCI, we focus on finding opportunities to support vulnerable populations through actionable data. With our Community Vulnerability Compass (CVC), we’ve been able to go beyond assumptions and deliver hard facts about the health of our community. Currently, hundreds of organizations around the state are either using or are set to receive access to the CVC where they can leverage powerful, data-driven insights.

Since its creation, we have been able to use the CVC in a variety of ways to reveal actionable insights about the health of communities around Texas. PCCI’s CVC provides an interactive dashboard that helps stakeholders—including community-based organizations (CBOs), safety-net hospitals, health systems, philanthropic organizations, governmental agencies, universities, and managed care organizations (MCOs)—to make informed decisions that enhance health outcomes and drive equity in service delivery. The CVC breaks through “what we think we know” to provide hard facts, including root causes of the overall state of any given area down to the block group.

Using Dallas County as a test case, we demonstrated how the CVC can surface community needs in relation to the area’s socioeconomic realities. For example, we examined the mental health state of Dallas County and the CVC found the areas of the county that have historically faced economic challenges were also the most vulnerable to mental health issues.

The CVC was also able to break through assumptions about communities experiencing high social or structural barriers. We found that in Dallas County, regardless of the economic condition, low vulnerable ZIP Codes had high vulnerability neighborhoods and high vulnerable ZIP codes had low vulnerability neighborhoods. In some areas you could see a high or low vulnerability area separated by a single street. This provides our community leaders an opportunity to reach all vulnerable areas, and it offers root cause insights into a neighborhood’s vulnerability. These insights allow us to appreciate the individual strengths of each area in our communities.

PCCI also conducted a full vulnerability assessment of the five largest counties in Texas (Bexar, Dallas, Harris, Tarrant and Travis counties) where we found more than 4.2 million residents live in high or very high vulnerability block groups. We learned that Bexar County had the most vulnerable block groups of the five counties where the most prominent root cause for its vulnerability is neighborhood safety, followed by chronic diabetes and households without vehicles. Additionally, the largest county, Harris, had the second most vulnerable block groups, but also had the highest number of low vulnerable block groups, with the most vulnerable block groups indicators being Neighborhood Safety, followed by Health Insurance Coverage and Mental Health.

These assessments are powerful examples of how the CVC is helping us gain a better understanding of our communities and the variety of root causes that drive the vulnerabilities throughout the state. Beyond analysis, we are seeing the CVC used in practical daily uses that have a direct impact on our residents.

For example, PCCI’s CVC has been incorporated into a variety of solutions throughout Texas, including adoption across the Parkland Health system, by the Dallas County Department of Health & Human Services, the University Heath (San Antonio) Transplant Center. Beyond dashboard access, for larger organizations, we offer the ability to reverse geocode individual-level data and append block group–level CVC insights. These insights can be integrated directly into electronic health records or customer relationship management systems, allowing organizations to use localized non-medical drivers of health (NMDoH) as a meaningful proxy at the individual level—enhancing precision in population health efforts, risk stratification, and targeted interventions.

PCCI’s CVC also serves as the backbone for the United Way of Metropolitan Dallas’ Data Capacity Building Initiative (DCBI), which is helping hundreds of organizations in North Texas turn insights into impact. The DCBI initiative has shown how the CVC is scalable and usable outside traditional healthcare settings. For instance, one CBO is using the CVC’s block group data to understand more about residents’ situations and tailor services more prescriptively. One organization has become better positioned to help victims and their children get out of harm’s way using the CVC, while another CBO is using the data to confirm service overuse in certain neighborhoods and service deserts in others.

An underlying goal for PCCI is to leverage the CVC to create a standard language and shared understanding around how NMDoH is utilized in Dallas County and beyond. This shared understanding would allow CBOs, governmental and healthcare providers to collaborate around a shared language of data in a more efficient manner.

Above all, the CVC fosters collaboration among diverse stakeholders by creating a shared understanding of community vulnerabilities and empowering organizations to advocate for and implement policy changes that address systemic issues. By addressing both health and overall equity, the CVC empowers safety-net hospitals and clinics serving vulnerable populations, funders, and CBOs to develop comprehensive strategies that enhance access to essential services, improve health outcomes, and ultimately promote social justice. In doing so, the CVC serves as a critical tool in advancing health equity, driving policy change to break cyclical inequity, and addressing systemic issues that impact the well-being of individuals and communities.

Learn more about the development of the CVC in PCCI’s recent publication in JAMIA which highlights how the CVC elevates insights and expands on the performance of existing tools that measure community socioeconomic variation.

Access the full research paper at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooaf059

About the Author

Lance Rather is the Senior Director of Product and Strategic Partnerships at PCCI. At PCCI he leverages his extensive expertise in technology and data analytics to develop and refine health-related products. Lance plays a crucial role in the creation and enhancement of tools like the Community Vulnerability Compass (CVC), focusing on making complex data accessible and actionable for healthcare providers and policymakers.

###

About Yolande Pengetnze

About Yolande Pengetnze