Why this post

More than a year ago, the data scientists at Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) committed to take the fight to COVID-19 by assisting North Texas residents, community leaders and public health officials through delivering actionable pandemic intelligence.

Many of us at PCCI and in the community have suffered the loss of family members, colleagues, coworkers, neighbors and friends. So with great relief we have witnessed tremendous scientific achievements in the development, approval and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines within a year. We have also seen the community evolve and adapt to life with COVID-19 and the actions expand from initial testing strategies to vaccine deployment, herd immunity projections and tracking, to now overcoming vaccination hesitancy and surveillance tracking of emerging variants, re-infections and individual/community immunity.

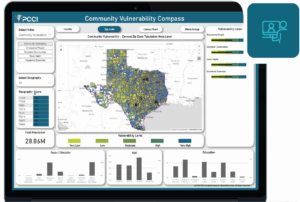

As our community and pandemic efforts evolve, so does the intelligence it needs. To meet that need, PCCI is evolving its technology and is pleased to announce the next phase of the Vulnerability Index.

What is the Vulnerability Index?

The Vulnerability Index is a measure of risk a community faces due to COVID-19. Higher risk means that people may be more likely to be infected with COVID-19, and if they do, they are more likely to experience symptoms and potentially face hospitalization and even death.

When the Vulnerability Index was first built, it covered factors correlated with COVID-19, including attributes in the community that don’t change quickly (like proportion of elderly population, people living with chronic conditions that are associated with COVID-19, and Non Medical Drivers of Health) as well as dynamic factors that increase immediate risk, like active COVID-19 cases and the mobility of the people living in the community.

How has the Vulnerability Index changed?

The North Texas community has evolved in two very important ways, and so the Vulnerability Index is changing as well.

-

- First, as with the rest of the world it has adopted mask-wearing, social distancing, hand washing, and other hygiene and behavioral recommendations from public health authorities to limit the spread of COVID-19. Combined with the full opening of the economy, this means that a mobility factor has less relevance in identifying risk, because people change their behavior when they are out shopping at the grocery store, working, visiting parks, and otherwise engaging in the community. Without these behavior adjustments, mobility would continue to be important to monitor and understand, but not a critical factor in predicting neighborhood vulnerability.

-

- Second, the introduction and uptake of the vaccine has started the process of lifting communities to herd immunity (HI), which is where the virus has a hard time finding people to infect because enough people have antibodies. As more people get vaccinated, there are fewer people in the community to become infected, and the community is less vulnerable.

An important caveat is that COVID-19 variants can continue to arise. PCCI is conducting ongoing surveillance on reinfections across Dallas County to assess the emergence of new variants, transmission and potential drop off of previously developed immunity. If this happens it means the mediating effect of the vaccination against COVID-19 risk may be decreased – so more people face infection risk. This is also captured in the updated Vulnerability Index.

How is the Vulnerability Index used?

The Vulnerability Index is used to inform how the communities and municipalities across Dallas County coordinate efforts to improve access to testing, vaccinations and create a path towards herd immunity. Below is a balloon plot, which shows cases on the horizontal axis and vaccinations on the vertical axis. It highlights HI progress in early April for ZIP codes across Dallas County. Each circle represents the current progress; each tail shows the improvement over two weeks. Upward “balloon” trajectory is favorable as it indicates that improvement was a result of vaccinations, not infections.

Source: The Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation

One thing that immediately jumps out is that ZIP codes with higher static vulnerability (or long-term risks in a community that do not change quickly such as age, medical comorbidities and social/economic factors) were slower at vaccine uptake. A potential reason for this is Non Medical Drivers of Health (NMDOH) – people who live in these zip codes may be in jobs that are not conducive to have the ability to take time off from work and to travel to vaccine sites to be vaccinated. This information is used by community organizers, public health officials, and health care providers to coordinate efforts and target each community in a way that removes barriers to vaccinations and target information and education via convenient and trusted sources.

Excelsior!

Ongoing vigilance against the virus remains key, and this includes getting vaccinated at your first available opportunity. As we enter the second summer in the pandemic, we at PCCI are committed to monitoring for COVID-19’s continued impact on the community, whether through improving the view into impacted communities, the impact of variants, reinfection risk, and more.

For more information about how PCCI has taken the fight to COVID-19, go to: https://pcci1.wpengine.com/taking-the-fight-to-covid-19/

###